[Originally posted on March 23, 2018, updated on April 11, 2018]

[Originally posted on March 23, 2018, updated on April 11, 2018]

Following more than six years of planning and public outreach, the City initiated the formal approval process for the Central SoMa Plan (Plan) at the Board of Supervisors and Planning Commission on February 27 and March 1, respectively. The Historic Preservation Commission (HPC) and Planning Commission held informational hearings on the Plan on March 21 and March 22, respectively. The HPC also considered initiation of the formal landmark designation process for certain buildings and districts identified during the Plan process. The Planning Commission is scheduled to consider the EIR and approvals on May 10, with the Board considering the legislation thereafter.

The Planning Commission’s approval package is over 600 pages, and the modifications proposed to the current land use controls are extensive. The summary below highlights some of the key changes proposed in the draft documents and describes those very generally. Please see the implementing legislation for specific language and details. As evidenced by Commissioner comment at the March 22 hearing, there is continued focus on the jobs/housing balance in the Plan area, with possible changes to increase the number of potential housing sites.

Plan Overview

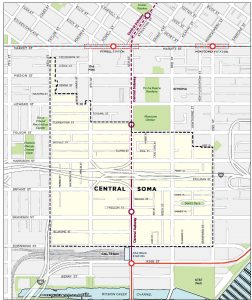

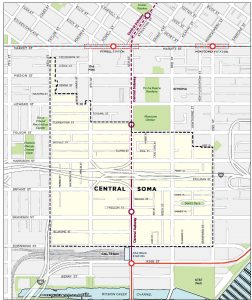

The Plan area is an approximately 230-acre site that runs roughly from 2nd Street to 6th Street, and from Market Street to Townsend Street, excluding certain areas north of Folsom Street that are part of the Downtown Plan. Very broadly, the Plan and implementing legislation would increase height and density and streamline zoning controls for certain properties. In exchange for this upzoning, the legislation would impose increased community benefits requirements, as described below. The legislative package includes amendments to the General Plan (including adoption of the Plan), Planning Code, Administrative Code, and Zoning Maps. The City’s analysis concludes that the Plan area has development capacity for up to 40,000 jobs and 7,000 housing units, and will generate about $2 billion in development impact fees.

Key Zoning Controls

Under the new zoning controls, the predominant new base zoning district would be Central SoMa Mixed Use-Office (CMUO). The CMUO zoning would largely replace relatively restrictive zoning districts with more flexible, mixed-use zoning. Certain subareas would remain principally designated for residential, PDR or other non-residential uses. The Plan area would also be subject to a Special Use District overlay (SUD). Some of the major SUD controls are: designating the largest sites (over 30,000 square feet) South of Harrison Street as predominantly non-residential, imposing new and replacement PDR requirements on certain larger sites, designating areas where nighttime entertainment is principally or conditionally permitted, and imposing active ground floor use requirements, including requiring “micro-retail” units of 1,000 square feet or less, and limiting formula retail uses. The SUD also extends the Transferable Development Rights (TDR) program to historic buildings and 100% affordable housing sites in the Plan area, and requires purchase of TDRs from the Plan area or the Downtown’s C-3 Districts for a portion of the FAR (between 3.0:1 and 4.25:1) for certain large (over 49,999 square feet) non-residential projects.

Current height limits in the Plan area are generally 85 feet or less, with heights up to 130 feet allowed on some parcels close to the Downtown Plan area. Under the Plan, in certain areas (generally near the Caltrain Station, along 4th Street, and adjacent to the Downtown Plan area and Rincon Hill), height limits are proposed up to 130-160 feet, subject to bulk controls to encourage building sculpting. A limited number of these parcels are proposed for towers 200-400 feet in height.

Exactions and Public Benefits

The Plan and its implementing legislation include detailed requirements regarding public benefits, urban design, streetscape and other key controls, including an “urban room” concept that encourages building area up to the sidewalk edge and a height equivalent to the width of the street. “Skyplane” (performance-based and setback) controls would apply to building heights beyond the base urban room. The controls also seek to limit the impact of the major towers through separation requirements and floorplate limits. Projects proposing more than 50,000 square feet of most non-residential uses (except PDR) are required to provide privately owned public open space (POPOS) or pay an in-lieu fee, similar to the Downtown C-3 Districts. The Plan and zoning controls also address sustainability (for example, through living roof, solar photovoltaic, thermal systems and greenhouse gas-free electricity requirements), as well as streetscape improvements and other strategies to limit parking and enhance pedestrian, bicycle and transit conditions. These include, for example, banning or limiting curb cuts, prioritizing on-site loading, and capping residential parking at 0.5 spaces per unit, and office parking at one space per 3,500 square feet.

The implementing legislation for the Plan also includes new development impact fees and taxes to fund proposed community benefits, including community facilities, transit, affordable housing, and open space. These exactions would be imposed by tier (Tier A 15-45 feet, Tier B 50-85 feet, and Tier C 90 feet or more). The Planning Department staff report includes a draft Public Benefits Program that summarizes the sources and uses of development impact fees and taxes generated by new development in the Plan area. Pages 18-21 include a fee analysis for prototypical non-residential and residential development, with the applicability and amount varying by Tier, and in some cases by square footage and other criteria. In addition to existing City-wide fees, the new development impact fees and taxes proposed for most Plan area projects include the Central SoMa Community Infrastructure Fee, the Central SoMa Community Services Facilities Fee, and participation in a Mello-Roos Community Facilities District (CFD). As explained above, TDR and POPOS requirements would also apply to certain non-residential projects.

Changes Proposed in Planning Department Staff Report

The Planning Department staff report for the April 12 hearing makes two recommended changes to address public and Commissioner comments regarding the jobs-housing balance. First, the zoning would be revised to allow two larger sites that were previously anticipated as primarily commercial to become primarily residential, resulting in approximately 640 additional units. Second, several additional sites would be designated Central SOMA Mixed Use Office, which is expected to yield another approximately 600 units, for a combined increase of over 1,200 units from what was originally proposed in the Plan.

We will continue to monitor the proposed legislation and implementing documents through the approval process.