On Friday, February 7, and Monday, February 10, 2020, the California Attorney General released proposed modified regulations in connection with the California Consumer Privacy Act (“CCPA”). The modified regulations provide businesses with some clarity, and arguable relief, from certain of the prior onerous regulatory obligations. Despite the modifications, however, there is still ambiguity about many aspects of the regulations, and the CCPA remains the most stringent privacy compliance law in effect in any state in the United States.

Below is a short summary of some of the more prominent changes to selected provisions of the regulations that may have an immediate effect on businesses. This summary is not meant to be an exhaustive list of the proposed modifications. These regulations are not final regulations, and additional changes may be made in the next few months as they are finalized. The deadline to submit written comments to the proposed modifications is February 25, 2020.

Changes to Definitions

“Personal Information” – Whether or not information collected by businesses is personal information now depends on how the business maintains the information. If the business maintains information in a manner that “identifies, relates to, describes, or is reasonably capable of being associated with, or could be reasonably linked, directly or indirectly, with a particular consumer or household,” the information is “personal information.” So, according to the regulations, if a business only collects IP addresses of visitors to its website but does not link or could not link the IP address to a particular consumer or household, the IP address would not be “personal information.”

This new definition tries to narrow the scope of “personal information” but remains ambiguous as to what information “could be” linked to a consumer or household. For example, collection of data through automated technology such as cookies, pixels, and web beacons is arguably anonymous and not linked to a consumer at the time of collection, but this data, when combined with enough other data points, could be reasonably linked to a particular consumer or household. For instance, if a consumer is logged into Facebook and browsing a website with the Facebook analytics tool called Facebook pixel in the same session, information collected on the website (including IP address, click patterns, etc.) may be attributed to the consumer’s Facebook profile. In this scenario, the collected data would presumably be “personal data.” Businesses will have to continue to analyze the types and amount of data they collect and how such data is used to determine if linkage to a consumer or household could reasonably be accomplished.

Categories of “Sources” and “Third Parties” – Businesses are now required to describe how the business collects personal information about consumers, and who it discloses the information to, with enough particularity to provide consumers with a “meaningful understanding.” Simply stating that the business collects information from or discloses information to “third parties” will not suffice. Businesses will have to explicitly list sources of the collected personal information and the types of third parties it shares that information with, such as advertising networks, internet service providers, data analytics providers, operating systems and platforms, social networks, government entities, and data brokers.

“Household” – Household means a person or group of people who: 1) reside at the same address; 2) share a common device or the same service provided by a business; and 3) are identified by the business as sharing the same group account or unique identifier.

“Signed” – The definition of “signed” means written attestation, declaration, or permission that is physically or electronically signed.

Changes to Consumer Rights and Requests Under the CCPA

“Requests to Delete” – The two-step process to confirm that a consumer wishes to delete his or her information is no longer required and is merely optional.

“Methods to Submit Request to Know and Requests to Delete” – Exclusively online businesses that have a direct relationship with consumers from whom they collect personal information only need to provide an email address for submitting requests to know. All other businesses must provide two methods, including a mandatory 1-800 number. For requests to delete, all businesses are still required to designate two or more acceptable methods. An interactive webform is an acceptable option but is no longer required for any consumer request.

Businesses that primarily interact with consumers in person should provide in-person methods such as printed forms that can be mailed, a tablet or computer portal for an online form, or a toll-free number to submit requests to know and delete.

“Right to Opt-Out” – If a business does not have proper notice of right to opt-out posted, it cannot sell personal information collected during that time unless it obtained affirmative authorization from the consumer.

“Request to Opt-Out” – A request to opt-out may now be made via global privacy controls or device settings. Any privacy control developed must clearly communicate or signal that a consumer intends to opt-out, so a pre-selected setting will not suffice. Consumers must affirmatively select their choice to opt-out. In case of a conflict with a consumer’s existing business-specific privacy setting or participation in a financial incentive program, the business shall respect the global privacy control but may notify the consumer of the conflict and give the consumer the choice to confirm the business-specific privacy setting or participation in the financial incentive program. Similarly, if a consumer initiates a transaction or attempts to use a product or service that requires the sale of information, a business can inform the consumer that the action requires the sale of personal information and provide instructions on how the consumer can opt-in.

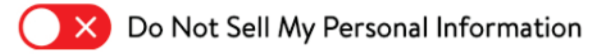

“Opt-Out Button” – If a business chooses to include the optional opt-out button, it must appear to the left of the “Do Not Sell My Personal Information” link, be approximately the same size as other buttons on the webpage, and explicitly look like this:

An example of a compliant opt-out button looks like:

“Methods to Submit Requests to Opt-Out” – Businesses should make Requests to Opt-Out easy for consumers and require minimal steps. Businesses cannot use a method that is designed with the purpose or substantial effect of subverting or impairing a consumer’s decision to opt-out.

“Time limits to Respond to Requests to Know and Requests to Delete and Opt-Out of Sale” – Businesses have some extra time to confirm receipt of consumer requests. Businesses must confirm receipt within 10 business days and can do so in the same manner in which the request was received. Similarly, businesses must now comply with a request to opt-out within 15 business days. The time to respond to requests to Know and Requests to Delete remains 45 calendar days from receipt of the request.

“Responding to Requests to Know” – A business does not need to search for personal information if: 1) it does not maintain the personal information in a searchable or reasonably accessible format; 2) it maintains the personal information only for legal or compliance purposes; 3) it does not sell information and does not use it for any commercial purpose; and 4) it describes to the consumer the categories of records that may contain personal information that it did not search because it met the above conditions. Note that all four of the above conditions must be met for the exception to apply.

“Responding to Requests to Delete” – Businesses no longer need to treat all requests to Delete as Requests to Opt-Out of Sale. However, if a business sells personal information and a consumer has made a request to delete, but not a request to opt-out, the business must ask the consumer if they would like to opt-out of sale of their personal information and will include a link to the right to opt-out or the contents of the notice of right to opt-out.

“Complying with a Request to Opt-Out” – Businesses that sell personal information no longer need to contact third parties to whom they sold a consumer’s personal information within 90 days prior to the business’s receipt of the consumer request. Instead, businesses now only need to notify those third parties that it sold personal information to after the consumer submitted the request but before the business complied with that request. Businesses must direct those third parties to not sell that consumer’s information.

Notice Requirements

Notice At Collection – For businesses that collect information online, the Notice at Collection may be given by a conspicuous link to the notice that must be posted on the introductory website page and on all webpages where personal information is collected. Businesses that collect information by telephone or in-person can provide the notice orally. For mobile users, a link to the notice must be provided on the download page and within the application such as within the settings menu. Mobile devices also require a “just-in-time” notice containing a summary of the categories of personal information being collected and a link to the full notice if the personal information collected is for a purpose that the consumer would not reasonably expect.

Notice of Right to Opt-Out of Sale of Personal Information – A business must explain the opt-out right and state whether or not it sells personal information. If it sells personal information, it must provide a link to the Notice of Opt-Out Right.

Notice of Financial Incentive – If a business does not offer a financial incentive or price difference related to disclosure, deletion, or sale of personal information, it does not have to provide notice of financial information. For businesses that do offer financial incentives, the business must explain to the consumer the material terms of the incentive the business is offering to allow the consumer to make an informed decision on whether to participate, and the notice must be readily available where consumers will encounter it before opting into the offered financial incentive. The notice must now include a description of the value of the consumer data.

“Non-Discrimination Business Practices and Requests to Delete or Opt-out” – Businesses must ensure that any financial incentive they offer is reasonably related to the value of the consumer data or the price difference would be considered discriminatory. If a business cannot calculate in good faith the value of consumer data or show that the financial incentive is reasonably related to the value of the consumer data, it shall not offer the financial incentive. To calculate the value of the data, a business can consider the value to all natural persons, not just consumers.

Businesses can deny a consumer’s request to delete information if the information is necessary to the business’s financial offering and is reasonably anticipated within the context of the business relationship between the parties. For example, if a business offers a loyalty program whereby consumers receive a $5 coupon via email for every $100 spent and a consumer submits a request to delete information and informs that business he or she wants to continue participating in the loyalty program, assuming the $5 is worth the value of the consumer data collected, the business may deny the request to delete the email address and amount spent by the consumer. This information is necessary and is reasonably anticipated within the context of the business relationship between the parties. This practice would not be considered discriminatory. However, if the business were offering discounts to consumers through a browser pop-up window while the consumer uses the website and the consumer were to submit a request to delete the email address on file, the business cannot deny the request because the email address is not necessary or reasonably aligned with the expectations of the consumer based on the parties’ business relationship. This practice would be discriminatory.

Privacy Policy – The privacy policy does not need to disclose the commercial purpose for which each category of information was collected. Rather, the privacy policy must only identify the categories of personal information collected in the preceding 12 months and identify the categories of personal information disclosed or sold to third parties in the preceding 12 months and, for each category of personal information sold or disclosed, provide the categories of third parties to whom the information was sold or disclosed.

The modified regulations also clarify that the privacy policy need only describe the consumer request verification process “generally.”

Purpose of Information Collected – Businesses cannot use a consumer’s personal information for any purpose materially different than those disclosed in the notice of collection. The addition of the terms “materially different” will limit the situations in which a business must provide notice and seek explicit consent when it has departed from using the information as previously disclosed.

Reasonable Accessibility to Consumers with Disabilities – Online notices must follow industry standards such as the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines, version 2.1 from the World Wide Consortium. These Guidelines provide accessibility guidance for consumers with cognitive or learning disabilities, low vision, and disabilities on mobile devices.

Collection of Employment-related Information – A business collecting employment-related information does not need to include a “Do Not Sell My Info” link, and may include a link to a business’s privacy policy for job applicants, employees or contractors in lieu of a link to the privacy policy for consumers.

Other Requirements

Personal Information Collected By Data Brokers – Businesses that buy information from data brokers registered with the State of California no longer need to perform due diligence about whether the business provided appropriate notice to the consumer and obtain signed attestations from the broker about how notice was given to consumers and request an example of the notice.

Service Providers – A business that collects information on behalf of another business may still fall under the “service provider” exemption of the CCPA if it uses the personal information collected for internal use to build or improve the quality of services provided that the use does not include building or modifying household or consumer profiles, or cleaning or augmenting data acquired from another source.

This provides much-needed relief for service providers especially in the cloud industry, that rely on access to such data to improve their services and product offerings. Service providers can also use personal information to retain and employ another service provider as a subcontractor (if the subcontractor meets the service provider requirements under the CCPA), as well as to detect data security incidents, protect against fraudulent or illegal activity, or to perform the services specified in the contract. However, Service Providers cannot sell data on behalf of a business when a consumer has opted out of the sale of their personal information with the business.

Service providers also no longer have the burden to respond to a consumer request to know or delete. Service providers can choose to do so on behalf of the business, or they can inform the consumer that the request cannot be completed because it was sent to the service provider.

Authorized Agent – A business’s privacy policy must now provide instructions on how an authorized agent can make requests under the CCPA (as opposed to instructing consumers how they can appoint an authorized agent, as required under the previous version of the regulations). Request to opt-out made by an authorized agent on behalf of a consumer must provide the authorized agent with written permission signed by the consumer. A business can also request the customer to directly confirm with the business that they provided the authorized agent permission to submit the request. An authorized agent now has the burden to implement and maintain reasonable security procedures and practices to protect consumer information and cannot use a consumer’s information for any purposes other than to fulfill the request, verification or fraud prevention.

Security – Businesses must implement and maintain reasonable security procedures and practices in maintaining records of consumer requests and how the business responded to such requests for at least 24 months. Such information shall only be maintained for record-keeping purposes except to review and modify the business’s compliance procedures. This information cannot be shared with any third party.

Identity Verification – A business may not require a consumer to pay a fee for the verification of the consumer’s request to know or delete. For example, a business may not require a consumer to submit a notarized affidavit to verify their identity unless the business compensates the consumer for the cost of notarization. If a business has no reasonable method by which it can verify the identity of a consumer, the business shall explain why it has no reasonable verification method in its privacy policy. The business must also evaluate and document on a yearly basis whether a reasonable method can be established.

If a business maintains personal information in a manner that is not associated with a named actual person, it may verify the request by asking the consumer to provide information that only the person associated with the information would know, including, if information is collected from a mobile application, requiring that the consumer respond to a notification sent to their device.

Consumer Metrics – Businesses that buy, receive, sell or disclose for a commercial purpose the personal information of over 10 million consumers in a calendar year must compile and disclose certain metrics regarding consumer requests in their privacy policies. This more than doubles the 4 million-consumer threshold triggering the metrics requirement under the previous version of the regulations.

Conclusion

Overall, the regulations provide some clarification and relief in terms of notice requirements, use of service providers, and submission of consumer requests. However, the modified regulations do not address many of the ambiguities regarding when sharing of personal information among businesses in the analytics or digital advertising context will be deemed a “sale” under the statute, nor has further guidance been provided regarding a uniform and sufficient process by which all businesses can securely and efficiently verify the identity of individuals making consumer requests. Although we may see some final tweaks before the July enforcement of the CCPA, businesses will likely have to continue to do the best they can to comply based on the current guidance.

For further information on how the modified regulations or the CCPA impacts your business, contact Cybersecurity & Data Privacy attorney Scott Hall at shall@coblentzlaw.com.